Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 37; 2025 > Article

- Original Article Health effects of weekend work on Korean workers: based on the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey

-

Ji-Hyeon Lee1

, Jin-Young Min2

, Jin-Young Min2 , Seok-Yoon Son1

, Seok-Yoon Son1 , Seung-Woo Ryoo1

, Seung-Woo Ryoo1 , Kyoung-Bok Min1,3,4,*

, Kyoung-Bok Min1,3,4,*

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2025;37:e31.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2025.37.e31

Published online: September 3, 2025

1Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Veterans Medical Research Institute, Veterans Health Service Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

3Integrated Major in Innovative Medical Science, Seoul National University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea

4Institute of Environmental Medicine, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea

- *Corresponding author: Kyoung-Bok Min Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea E-mail: minkb@snu.ac.kr

© 2025 Korean Society of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,856 Views

- 88 Download

Abstract

-

Background Although weekend work makes up a significant part of work patterns in modern society, research on the health effects of weekend work is relatively limited compared to other types of nonstandard work. This study was conducted to examine the impact of weekend work on the health of Korean workers, aiming to provide evidence to support the development of welfare policies that promote workers’ health.

-

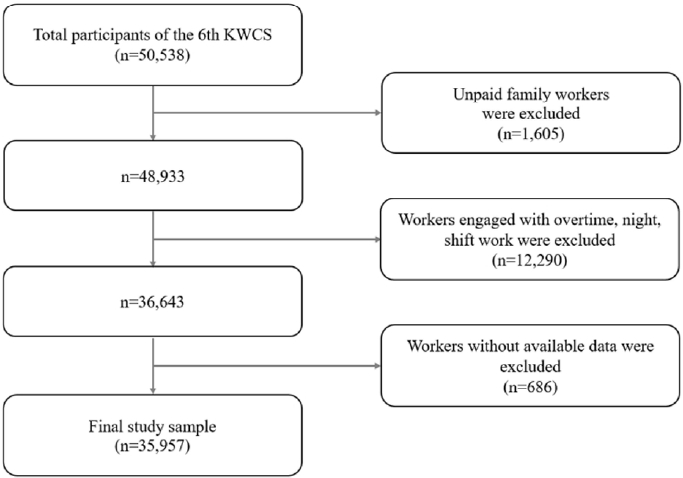

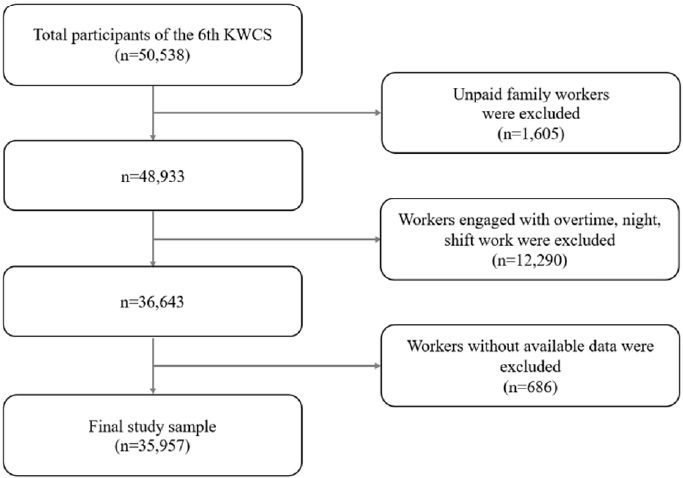

Methods This study was conducted using data from the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey, targeting 35,957 Korean workers who met the research criteria. Based on the survey responses, information was collected on weekend work status and health outcomes, including general health, musculoskeletal pain, headaches or eye pain, fatigue, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, absenteeism and presenteeism. To examine the association between weekend work and health outcome variables, logistic regression analysis was performed adjusting for sociodemographic and occupational characteristics, with additional stratified analyses conducted according to employment status.

-

Results Among the final study population, 11,255 workers, accounting for 30.5% of the total, were weekend workers. After adjusting for sociodemographic and occupational characteristics, weekend work was found to be significantly associated with depression (odds ratio [OR]: 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.00–1.18), anxiety (OR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.16–1.58), musculoskeletal pain (OR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.34–1.58), fatigue (OR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.36–1.62), absenteeism (OR: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.43–2.03), and presenteeism (OR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.62–2.04). The health effects of weekend work differed between the self-employed and employees, as shown in the results of the stratified analysis.

-

Conclusions Weekend work was found to increase the risk of both physical and mental health problems of Korean workers, and the effect varied according to employment status. There is a need to design a comprehensive occupational health policy that reflects the characteristics of different employment statuses.

BACKGROUND

METHODS

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

Abbreviations

-

Funding

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (grant number, RS-2022-NR070347, RS-2024-00338688).

-

Competing interests

Kyoung-Bok Min, contributing editor of the Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Lee JH, Min KB. Data curation: Lee JH, Ryoo SW. Formal analysis: Lee JH. Funding acquisition: Min KB. Methodology: Lee JH, Min KB. Software: Lee JH. Validation: Min JY, Min KB. Visualization: Lee JH, Son SY. Writing - original draft: Lee JH, Min JY. Writing - review & editing: Min KB, Ryoo SW, Son SY.

-

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute of Korea.

NOTES

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Table 2.

Supplementary Table 3.

| Characteristic | Total |

Weekend work |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| Total | 36,920 | 25,665 (69.5) | 11,255 (30.5) | |

| Sex | <0.001*** | |||

| Male | 20,597 (55.8) | 13,835 (53.9) | 6,763 (60.1) | |

| Female | 16,322 (44.2) | 11,830 (46.1) | 4,492 (39.9) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001*** | |||

| 15–29 | 5,110 (13.8) | 3,400 (13.3) | 1,711 (15.2) | |

| 30–39 | 7,439 (20.2) | 5,651 (22.0) | 1,788 (15.9) | |

| 40–49 | 8,914 (24.1) | 6,499 (25.3) | 2,415 (21.5) | |

| 50–59 | 8,379 (22.7) | 5,578 (21.7) | 2,800 (24.9) | |

| ≥60 | 7,078 (19.2) | 4,536 (17.7) | 2,541 (22.6) | |

| Education | <0.001*** | |||

| High-school graduate or lower | 15,909 (43.1) | 9,670 (37.7) | 6,240 (55.5) | |

| College graduate | 20,964 (56.8) | 15,959 (62.3) | 5,005 (44.5) | |

| Monthly income (10,000 KRW) | <0.001*** | |||

| <200 | 10,806 (29.3) | 7,258 (29.8) | 3,547 (32.9) | |

| 200–299 | 10,491 (28.4) | 7,092 (29.1) | 3,399 (31.5) | |

| 300–399 | 7,375 (20.0) | 5,193 (21.3) | 2,182 (20.2) | |

| ≥400 | 6,506 (17.6) | 4,841 (19.9) | 1,664 (15.4) | |

| Status of employment | <0.001*** | |||

| Self-employed | 6,188 (16.8) | 2,669 (10.4) | 3,520 (31.3) | |

| Employee | 30,731 (83.2) | 22,996 (89.6) | 7,735 (68.7) | |

| Work hours per week | 0.003** | |||

| <40 | 9,277 (25.1) | 6,274 (24.5) | 3,003 (26.7) | |

| 40–52 | 27,642 (74.9) | 19,391 (75.6) | 8,252 (73.3) | |

| Health outcomes |

Weekend work |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| General health | |||

| Poor | 929 (3.6) | 527 (4.7) | <0.001*** |

| Psychological health | |||

| Sleep disorder | 1,901 (7.4) | 967 (8.6) | 0.006** |

| Depression | 7,590 (29.6) | 3,734 (33.2) | <0.001*** |

| Anxiety | 1,105 (4.3) | 656 (5.8) | <0.001*** |

| Physical health | |||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 9,133 (35.6) | 5,272 (46.8) | <0.001*** |

| Headache or eye pain | 4,965 (19.4) | 1,979 (17.6) | 0.009** |

| Fatigue | 5,251 (20.5) | 3,196 (28.4) | <0.001*** |

| Sickness absence | |||

| Have experienced | 759 (3.0) | 551 (4.9) | <0.001*** |

| Presenteeism | |||

| Have experienced | 2,170 (8.5) | 1,585 (14.1) | <0.001*** |

| Health outcomes |

Crude model |

Adjusted modela |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| General health | ||||

| Poor | 1.31 (1.13–1.52) | <0.001*** | 1.11 (0.95–1.29) | 0.210 |

| Psychological health | ||||

| Sleep disorder | 1.18 (1.05–1.32) | 0.006** | 1.11 (0.98–1.27) | 0.093 |

| Depression | 1.18 (1.10–1.27) | <0.001*** | 1.08 (1.00–1.18) | 0.049* |

| Anxiety | 1.38 (1.18–1.60) | <0.001*** | 1.35 (1.16–1.58) | <0.001*** |

| Physical health | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1.60 (1.49–1.71) | <0.001*** | 1.45 (1.34–1.58) | <0.001*** |

| Headache or eye pain | 0.89 (0.82–0.97) | 0.009** | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 0.607 |

| Fatigue | 1.54 (1.43–1.67) | <0.001*** | 1.49 (1.36–1.62) | <0.001*** |

| Sickness absence | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.69 (1.41–2.01) | <0.001*** | 1.70 (1.43–2.03) | <0.001*** |

| Presenteeism | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.77 (1.59–1.98) | <0.001*** | 1.82 (1.62–2.04) | <0.001*** |

| Health outcomes |

Crude model |

Adjusted modela |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Self-employed | ||||

| General health | ||||

| Poor | 1.50 (1.19–1.90) | <0.001*** | 1.31 (1.00–1.72) | 0.053 |

| Psychological health | ||||

| Sleep disorder | 1.12 (0.90–1.38) | 0.307 | 1.03 (0.82–1.30) | 0.796 |

| Depression | 1.07 (0.92–1.25) | 0.362 | 0.98 (0.83–1.15) | 0.758 |

| Anxiety | 1.19 (0.90–1.58) | 0.214 | 1.17 (0.89–1.55) | 0.264 |

| Physical health | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1.70 (1.46–1.97) | <0.001*** | 1.47 (1.24–1.73) | <0.001*** |

| Headache or eye pain | 0.84 (0.70–1.03) | 0.087 | 0.86 (0.71–1.06) | 0.151 |

| Fatigue | 1.49 (1.25–1.78) | <0.001*** | 1.37 (1.15–1.63) | <0.001*** |

| Sickness absence | ||||

| Have experienced | 2.35 (1.63–3.38) | <0.001*** | 2.34 (1.58–3.46) | <0.001*** |

| Presenteeism | ||||

| Have experienced | 2.26 (1.77–2.89) | <0.001*** | 2.20 (1.71–2.84) | <0.001*** |

| Employee | ||||

| General health | ||||

| Poor | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.238 | 0.97 (0.79–1.20) | 0.779 |

| Psychological health | ||||

| Sleep disorder | 1.07 (0.93–1.24) | 0.350 | 1.13 (0.97–1.31) | 0.116 |

| Depression | 1.15 (1.05–1.26) | 0.002** | 1.11 (1.01–1.22) | 0.025* |

| Anxiety | 1.37 (1.14–1.64) | <0.001*** | 1.40 (1.17–1.68) | <0.001*** |

| Physical health | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1.40 (1.29–1.53) | <0.001*** | 1.45 (1.32–1.59) | <0.001*** |

| Headache or eye pain | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 0.051 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 0.983 |

| Fatigue | 1.47 (1.34–1.62) | <0.001*** | 1.52 (1.38–1.67) | <0.001*** |

| Sickness absence | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.57 (1.28–1.91) | <0.001*** | 1.59 (1.30–1.94) | <0.001*** |

| Presenteeism | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.65 (1.46–1.87) | <0.001*** | 1.75 (1.54–1.99) | <0.001*** |

- 1. Bureau of Labor Statistics. American time use survey-2022 results, Table 4. Employed persons working and time spent working on days worked by full- and part-time status and sex, jobholding status, educational attainment, and day of week, 2023 annual averages. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/atus_06222023.pdf. Updated 2023. Accessed May 28, 2025.

- 2. Eurostat. Work on weekends by sex, age, professional status and occupation. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/lfsa_qoe_3b3. Updated 2024. Accessed May 28, 2025.

- 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Characteristics of employment, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/earnings-and-working-conditions/characteristics-employment-australia/latest-release. Updated 2024. Accessed May 28, 2025.

- 4. Korea Occupational Safety & Health Agency. Korean working conditions survey, 2020, work on saturdays. https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=380&tblId=DT_380002_D014_6TH&conn_path=I2. Updated 2022. Accessed May 28, 2025.

- 5. Korea Occupational Safety & Health Agency. Korean working conditions survey, 2020, work on sundays. https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=380&tblId=DT_380002_D013_6TH&conn_path=I2. Updated 2022. Accessed May 28, 2025.

- 6. Zeytinoglu IU, Cooke GB. Who is working at weekends? Determinants of regular weekend work in Canada. In: Boulin JV, Lallement M, Messenger J, Michon F, editors. Decent Working Time: New Trends, New Issues. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2006, 395–416.

- 7. Berg P, Bosch G, Charest J. Working-time configurations: a framework for analyzing diversity across countries. ILR Rev 2014;67(3):805–37.

- 8. Anttila T, Oinas T. 24/7 Society: the new timing of work?. In: Tammelin M, editor. Family, Work and Well-Being: Emergence of New Issues. Cham, Germany: Springer International Publishing; 2018, 63–76.

- 9. Kalil A, Ziol-Guest KM, Levin Epstein J. Nonstandard work and marital instability: evidence from the national longitudinal survey of youth. J Marriage Fam 2010;72:1289–300.Article

- 10. Jamal M. Burnout, stress and health of employees on non‐standard work schedules: a study of Canadian workers. Stress Health 2004;20(3):113–9.Article

- 11. Davis KD, Goodman WB, Pirretti AE, Almeida DM. Nonstandard work schedules, perceived family well-being, and daily stressors. J Marriage Fam 2008;70(4):991–1003.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Sato K, Kuroda S, Owan H. Mental health effects of long work hours, night and weekend work, and short rest periods. Soc Sci Med 2020;246:112774.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Nikolova M, Nikolaev B, Boudreaux C. Being your own boss and bossing others: the moderating effect of managing others on work meaning and autonomy for the self-employed and employees. Small Bus Econ 2023;60(2):463–83.ArticlePDF

- 14. Hyytinen A, Ruuskanen OP. Time use of the self‐employed. Kyklos 2007;60(1):105–22.Article

- 15. Parker SC, Belghitar Y, Barmby T. Wage uncertainty and the labour supply of self‐employed workers. Econ J 2005;115(502):C190–207.Article

- 16. Zhang N, He X. Role stress, job autonomy, and burnout: the mediating effect of job satisfaction among social workers in China. J Soc Serv Res 2022;48(3):365–75.Article

- 17. Westergren A, Broman JE, Hellstrom A, Fagerstrom C, Willman A, Hagell P. Measurement properties of the minimal insomnia symptom scale as an insomnia screening tool for adults and the elderly. Sleep Med 2015;16(3):379–84.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Topp CW, Ostergaard SD, Sondergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84(3):167–76.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. Wirtz A, Nachreiner F, Rolfes K. Working on Sundays-effects on safety, health, and work-life balance. Chronobiol Int 2011;28(4):361–70.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Greubel J, Arlinghaus A, Nachreiner F, Lombardi DA. Higher risks when working unusual times? A cross-validation of the effects on safety, health, and work-life balance. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2016;89(8):1205–14.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Thomas C, Power C. Shift work and risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a study at age 45 years in the 1958 British birth cohort. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25(5):305–14.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Weston G, Zilanawala A, Webb E, Carvalho LA, McMunn A. Long work hours, weekend working and depressive symptoms in men and women: findings from a UK population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019;73(5):465–74.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Bittman M. Sunday working and family time. Lab Ind 2005;16(1):59–81.Article

- 24. Lass I, Wooden M. Weekend work and work-family conflict: evidence from Australian panel data. J Marriage Fam 2022;84(1):250–72.Article

- 25. Frone MR. Work-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: the National Comorbidity Survey. J Appl Psychol 2000;85(6):888–95.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Vinberg S, Landstad BJ, Tjulin A, Nordenmark M. Sickness presenteeism among the Swedish self-employed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 2021;12:723036.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 27. Hansen CD, Andersen JH. Going ill to work: what personal circumstances, attitudes and work-related factors are associated with sickness presenteeism? Soc Sci Med 2008;67(6):956–64.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Lechmann DS, Schnabel C. Absence from work of the self‐employed: a comparison with paid employees. Kyklos 2014;67(3):368–90.ArticlePDF

- 29. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Admin Sci Q 1979;24:285–308.Article

- 30. Snyder LA, Krauss AD, Chen PY, Finlinson S, Huang YH. Occupational safety: application of the job demand-control-support model. Accid Anal Prev 2008;40(5):1713–23.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Hessels J, Rietveld CA, van der Zwan P. Self-employment and work-related stress: the mediating role of job control and job demand. J Bus Ventur 2017;32(2):178–96.Article

- 32. Stephan U, Roesler U. Health of entrepreneurs versus employees in a national representative sample. J Occup Org Psychol 2010;83(3):717–38.Article

- 33. Tennant C. Work-related stress and depressive disorders. J Psychosom Res 2001;51(5):697–704.ArticlePubMed

- 34. Wang J. Work stress as a risk factor for major depressive episode(s). Psychol Med 2005;35(6):865–71.ArticlePubMed

- 35. Godin I, Kittel F, Coppieters Y, Siegrist J. A prospective study of cumulative job stress in relation to mental health. BMC Public Health 2005;5:67.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 36. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Self-employment rate. https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/self-employment-rate.html. Updated 2023. Accessed May 28, 2025.

- 37. Park J, Han B, Kim Y. Comparison of occupational health problems of employees and self-employed individuals who work in different fields. Arch Environ Occup Health 2020;75(2):98–111.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Heymann J, Rho HJ, Schmitt J, Earle A. Ensuring a healthy and productive workforce: comparing the generosity of paid sick day and sick leave policies in 22 countries. Int J Health Serv 2010;40(1):1–22.ArticlePubMedPDF

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1.

| Characteristic | Total | Weekend work |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| Total | 36,920 | 25,665 (69.5) | 11,255 (30.5) | |

| Sex | <0.001 |

|||

| Male | 20,597 (55.8) | 13,835 (53.9) | 6,763 (60.1) | |

| Female | 16,322 (44.2) | 11,830 (46.1) | 4,492 (39.9) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 |

|||

| 15–29 | 5,110 (13.8) | 3,400 (13.3) | 1,711 (15.2) | |

| 30–39 | 7,439 (20.2) | 5,651 (22.0) | 1,788 (15.9) | |

| 40–49 | 8,914 (24.1) | 6,499 (25.3) | 2,415 (21.5) | |

| 50–59 | 8,379 (22.7) | 5,578 (21.7) | 2,800 (24.9) | |

| ≥60 | 7,078 (19.2) | 4,536 (17.7) | 2,541 (22.6) | |

| Education | <0.001 |

|||

| High-school graduate or lower | 15,909 (43.1) | 9,670 (37.7) | 6,240 (55.5) | |

| College graduate | 20,964 (56.8) | 15,959 (62.3) | 5,005 (44.5) | |

| Monthly income (10,000 KRW) | <0.001 |

|||

| <200 | 10,806 (29.3) | 7,258 (29.8) | 3,547 (32.9) | |

| 200–299 | 10,491 (28.4) | 7,092 (29.1) | 3,399 (31.5) | |

| 300–399 | 7,375 (20.0) | 5,193 (21.3) | 2,182 (20.2) | |

| ≥400 | 6,506 (17.6) | 4,841 (19.9) | 1,664 (15.4) | |

| Status of employment | <0.001 |

|||

| Self-employed | 6,188 (16.8) | 2,669 (10.4) | 3,520 (31.3) | |

| Employee | 30,731 (83.2) | 22,996 (89.6) | 7,735 (68.7) | |

| Work hours per week | 0.003 |

|||

| <40 | 9,277 (25.1) | 6,274 (24.5) | 3,003 (26.7) | |

| 40–52 | 27,642 (74.9) | 19,391 (75.6) | 8,252 (73.3) | |

| Health outcomes | Weekend work |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| General health | |||

| Poor | 929 (3.6) | 527 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Psychological health | |||

| Sleep disorder | 1,901 (7.4) | 967 (8.6) | 0.006 |

| Depression | 7,590 (29.6) | 3,734 (33.2) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1,105 (4.3) | 656 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Physical health | |||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 9,133 (35.6) | 5,272 (46.8) | <0.001 |

| Headache or eye pain | 4,965 (19.4) | 1,979 (17.6) | 0.009 |

| Fatigue | 5,251 (20.5) | 3,196 (28.4) | <0.001 |

| Sickness absence | |||

| Have experienced | 759 (3.0) | 551 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Presenteeism | |||

| Have experienced | 2,170 (8.5) | 1,585 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Health outcomes | Crude model |

Adjusted model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| General health | ||||

| Poor | 1.31 (1.13–1.52) | <0.001 |

1.11 (0.95–1.29) | 0.210 |

| Psychological health | ||||

| Sleep disorder | 1.18 (1.05–1.32) | 0.006 |

1.11 (0.98–1.27) | 0.093 |

| Depression | 1.18 (1.10–1.27) | <0.001 |

1.08 (1.00–1.18) | 0.049 |

| Anxiety | 1.38 (1.18–1.60) | <0.001 |

1.35 (1.16–1.58) | <0.001 |

| Physical health | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1.60 (1.49–1.71) | <0.001 |

1.45 (1.34–1.58) | <0.001 |

| Headache or eye pain | 0.89 (0.82–0.97) | 0.009 |

0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 0.607 |

| Fatigue | 1.54 (1.43–1.67) | <0.001 |

1.49 (1.36–1.62) | <0.001 |

| Sickness absence | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.69 (1.41–2.01) | <0.001 |

1.70 (1.43–2.03) | <0.001 |

| Presenteeism | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.77 (1.59–1.98) | <0.001 |

1.82 (1.62–2.04) | <0.001 |

| Health outcomes | Crude model |

Adjusted model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Self-employed | ||||

| General health | ||||

| Poor | 1.50 (1.19–1.90) | <0.001 |

1.31 (1.00–1.72) | 0.053 |

| Psychological health | ||||

| Sleep disorder | 1.12 (0.90–1.38) | 0.307 | 1.03 (0.82–1.30) | 0.796 |

| Depression | 1.07 (0.92–1.25) | 0.362 | 0.98 (0.83–1.15) | 0.758 |

| Anxiety | 1.19 (0.90–1.58) | 0.214 | 1.17 (0.89–1.55) | 0.264 |

| Physical health | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1.70 (1.46–1.97) | <0.001 |

1.47 (1.24–1.73) | <0.001 |

| Headache or eye pain | 0.84 (0.70–1.03) | 0.087 | 0.86 (0.71–1.06) | 0.151 |

| Fatigue | 1.49 (1.25–1.78) | <0.001 |

1.37 (1.15–1.63) | <0.001 |

| Sickness absence | ||||

| Have experienced | 2.35 (1.63–3.38) | <0.001 |

2.34 (1.58–3.46) | <0.001 |

| Presenteeism | ||||

| Have experienced | 2.26 (1.77–2.89) | <0.001 |

2.20 (1.71–2.84) | <0.001 |

| Employee | ||||

| General health | ||||

| Poor | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.238 | 0.97 (0.79–1.20) | 0.779 |

| Psychological health | ||||

| Sleep disorder | 1.07 (0.93–1.24) | 0.350 | 1.13 (0.97–1.31) | 0.116 |

| Depression | 1.15 (1.05–1.26) | 0.002 |

1.11 (1.01–1.22) | 0.025 |

| Anxiety | 1.37 (1.14–1.64) | <0.001 |

1.40 (1.17–1.68) | <0.001 |

| Physical health | ||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1.40 (1.29–1.53) | <0.001 |

1.45 (1.32–1.59) | <0.001 |

| Headache or eye pain | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 0.051 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 0.983 |

| Fatigue | 1.47 (1.34–1.62) | <0.001 |

1.52 (1.38–1.67) | <0.001 |

| Sickness absence | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.57 (1.28–1.91) | <0.001 |

1.59 (1.30–1.94) | <0.001 |

| Presenteeism | ||||

| Have experienced | 1.65 (1.46–1.87) | <0.001 |

1.75 (1.54–1.99) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as weighted frequency (%).

Values are presented as weighted frequency (%).

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. Adjusted for sex, age, education, monthly income, status of employment, work hours per week.

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. Adjusted for sex, age, education, monthly income, status of employment, work hours per week.

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite