Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 37; 2025 > Article

- Review The status and implications of paid sick leave and sickness benefits in OECD countries

-

Jaehoon Lee1, Jinwoo Lee2,*

, Sang Baek Koh3,*

, Sang Baek Koh3,*

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2025;37:e21.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2025.37.e21

Published online: July 28, 2025

1Public Policy Institute for People, Seoul, Korea

2Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hanil General Hospital, Seoul, Korea

3Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea

- *Corresponding author: Jinwoo Lee Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hanil General Hospital, 308 Uicheon-ro, Dobong-gu, Seoul 01450, Korea E-mail: uzhamjinbo@gmail.com

- Sang Baek Koh Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, 20 Ilsan-ro, Wonju 26426, Korea E-mail: kohhj@yonsei.ac.kr

© 2025 Korean Society of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 2,357 Views

- 99 Download

Abstract

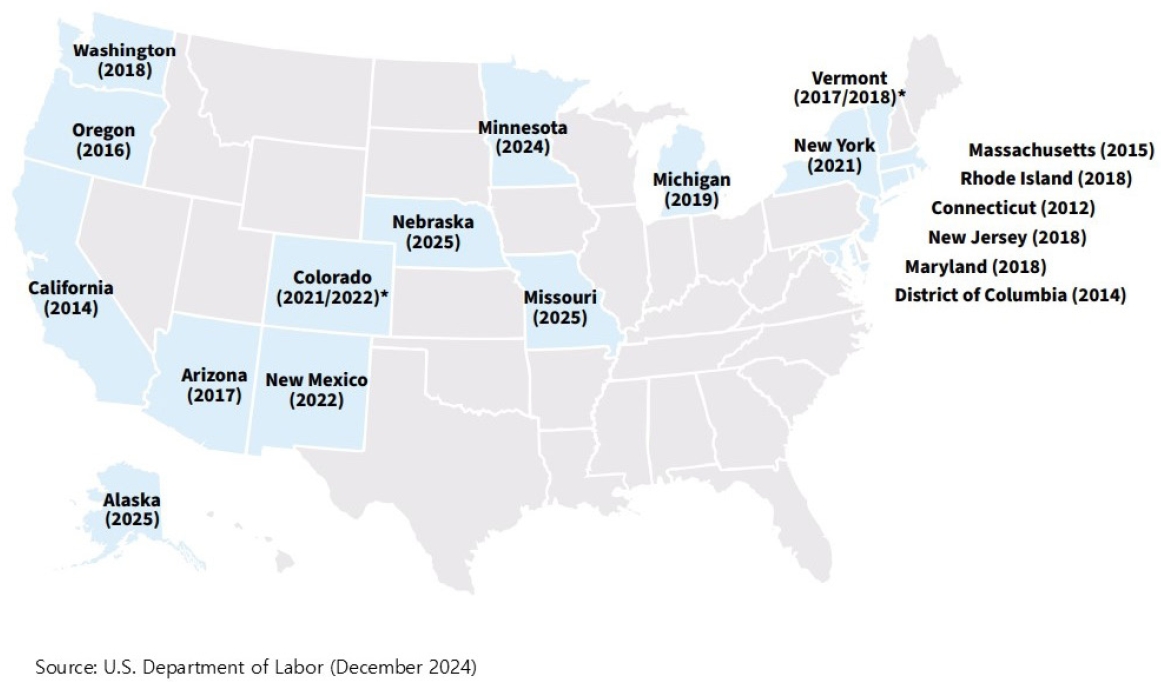

- The experience of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has highlighted the importance of paid sick leave and sickness benefits, and is creating an international movement to introduce or improve real-world systems. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries except Korea and the United States already have statutory paid sick leave or sickness benefits, with the United Kingdom extending statutory paid sick leave to low-income workers in 2025, and Ireland introducing statutory paid sick leave in 2023. In the United States, 19 states, including Minnesota in 2024 and Alaska and Missouri in 2025, as well as the Washington, D.C., have introduced statutory paid sick leave (as of December 2024). Furthermore, an analysis of 33 OECD countries with statutory paid sick leave or sickness benefits suggests that 21 countries comply with the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention standards for adequacy of benefits and comprehensiveness of coverage, while six countries with social assistance have high comprehensiveness of coverage but low adequacy of benefits. There was not a single country with a program that had low levels of both benefit adequacy and coverage. In Korea, the pilot sickness benefit program has been extended until 2027, and the system has been delayed. The principles of benefit adequacy and coverage comprehensiveness must be upheld for the purpose and intent of the program to ensure adequate care and rest. Consequently, in addition to adhering to the standards outlined in the ILO Convention, the implementation of paid sick leave should be codified in legislation to enhance employer accountability.

BACKGROUND

METHODS

RESULTS

CONCLUSIONS

Abbreviations

COVID-19

ILO

ISSA

OECD

-

Competing interests

Sang Baek Koh, contributing editor of the Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Lee J (Jaehoon Lee). Data curation: Lee J (Jaehoon Lee). Methodology/Formal analysis: Lee J (Jaehoon Lee). Project administration: Lee J (Jinwoo Lee). Funding acquisition: Koh SB. Writing - original draft: Lee J (Jaehoon Lee). Writing - review & editing: Lee J (Jaehoon Lee).

NOTES

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Data 1.

| Country | Statutory paid sick leave | Sickness benefit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit | Coverage | Waiting period | Benefit period (max) | Financial resources (worker/employer) | Expenditure (% GDP)a | |||

| Non-regular workers | Self-employed | |||||||

| Australia | 10 days/regular workers | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 7 days | 9 months | Taxes | N/A |

| Austria | 16 weeks | 50%–75% | △ | × | N/A | 52 weeks | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Belgium | 30 days | 60% | ○ | ○ | 15–30 days | 1 year | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Canada | Varies by province | 55% | ○ | × | 7 days | 26 weeks | Worker < Employer | 0.1 |

| Chile (Private) | 3 days | 100% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | Worker | 0.1 | |

| Colombia | 2 days | 50%–66.6% | ○ | ○ | 2 days | 180 days | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Costa Rica | × | 60% | ○ | ○ | N/A | 26 weeks | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Czech Republic | 14 days | 60%–72% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 380 days | Employer | 0.8 |

| Denmark | 30 days | Flat-rate | ○ | △ | Self-employed (2 weeks) | 22 weeks | Taxes | 0.8 |

| Estonia | Days 4–8 | 70% | ○ | ○ | 9 days | 182 days | Employer | 0.5 |

| Finland | 10 days | 70% | ○ | ○ | 10 days | 300 days | Worker > Employer | 0.4 |

| France | 3 days | 50% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 12 months (3 years) | Employer | 0.7 |

| Germany | 6 weeks | 70% | ○ | ○ | 6 weeks | 78 weeks | Worker = Employer | 0.4 |

| Greece | × | 50% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 720 days | Worker > Employer | 0.2 |

| Hungary | 15 days | 50% | ○ | ○ | N/A | 1 year | Worker < Employer | 0.5 |

| Iceland | 14 days | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 14 days | 52 weeks | Taxes | 0.0 |

| Ireland | 5 days (introduced in 2023) | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 6 days | 52 weeks (2 years) | Worker < Employer | 0.3 |

| Israel | 90 days | × | × | × | × | × | × | N/A |

| Italy | × | 50%–66.6% | △ | × | 3 days | 180 days | Employer | 0.2 |

| Japan | × | 66.67% | × | × | 3 days | 18 months | Worker = Employer | 0.1 |

| Korea | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | N/A |

| Latvia | Days 2–10 | 80% | ○ | ○ | 10 days | 52 weeks | Worker < Employer | 1.0 |

| Lithuania | 2 days | 80% | ○ | ○ | 2 days | 1 year | Employer | 0.8 |

| Luxembourg | 77 days | 100% | ○ | ○ | 77 days | 52 weeks | Worker = Employer | 0.4 |

| Mexico | × | 60% | ○ | × | 3 days | 52 weeks (78 weeks) | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Netherlands | 104 weeks | 70%–100% | ○ | × | N/A | 104 weeks | Employer | 0.3 |

| New Zealand | 5 days | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 2 weeks | 52 weeks reassessment | Taxes | |

| Norway | 16 days | 100%/75% (workplace/region) | ○ | ○ | 16 days | 52 weeks/248 days (workplace/region) | Worker < Employer | 1.0 |

| Poland | 33 days/14 days (under 50/50 or older) | 80%/70% (under 50/50 or older) | ○ | △ | 33 days/15 days | 182 days | Worker | 0.9 |

| Portugal | × | 55%–75% | ○ | △ | 3 days/10 days | 1,950 days/1 year (workplace/region) | Worker < Employer | 0.6 |

| Slovakia | 11 days | 55% | ○ | ○ | 11 days | 52 weeks | Worker = Employer | 0.8 |

| Slovenia | 30 days | 70%–80% | ○ | ○ | 30 days | No limits | Worker < Employer | 1.2 |

| Spain | Days 4–15 | 75% | ○ | × | 4 days | 12 months | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Switzerland | 3 weeks–1 year | × | × | × | × | × | × | 0.9 |

| Türkiye | 7 days | 66.7% | ○ | ○ | 2 days | No limits | Employer | 0.8 |

| United Kingdom | Day 4–week 28 | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 28 weeks | Taxes | 0.1 |

| United States | Varies by state government | × | × | × | × | × | × | N/A |

The data were primarily based on the “Social Security Programs throughout the World” published by Social Security Administration (SSA) and International Social Security Association (ISSA) (https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/progdesc/ssptw/)2, and were supplemented by Lee5 and Lim et al.6 OECD countries, more recent information was updated using ISSA’s Country Profiles database (https://www.issa.int/databases/country-profiles)3. In addition, selected reform cases were supplemented with official sources from relevant government ministries in each country.

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; N/A: not available; ×: Enrollment restricted; ○: Enrollment allowed; △: Optional enrollment.

aPublic cash expenditure on sickness benefits as a percentage of GDP is from OECD SOCX (visited on April 19, 2025).

| Comprehensiveness of coverage (low) | Comprehensiveness of coverage (high) | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| (Ⅱ) Austria, Japan, Canada, Mexico, Netherlands, Spain | (Ⅰ) Belgium, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Türkiye | Adequacy of benefits (high) |

| (Ⅲ) (United States, Korea)a | (Ⅳ) Australia, Iceland, Ireland, New Zealand, Denmark, United Kingdom | Adequacy of benefits (low) |

- 1. International Labour Organization. Sickness Benefits during Sick Leave and Quarantine: Country Responses and Policy Considerations in the Context of COVID-19. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2020.

- 2. International Social Security Association (ISSA); U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA). Social Security Programs throughout the World: Asia and the Pacific, 2018. SSA Publication No. 13-11802. Washington, DC: U.S. Social Security Administration; 2019.

- 3. International Social Security Association (ISSA). Country profiles database. Geneva, Switzerland: International Social Security Association; updated continuously. https://www.issa.int/databases/country-profiles/. Updated 2025. Accessed May 13, 2025.

- 4. International Labour Organization. Towards Universal Health Coverage: Social Health Protection Principles. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2020.

- 5. Lee JH. Paid Sick Leave and Sickness Benefits Abroad and the Introduction Direction for Korea: Ensuring the Right to Rest and Recover When Ill. Issue Paper 2020-02. Seoul, Korea: Public Policy Institute for People, Korean Public Service and Transport Workers' Union; 2020.

- 6. Lim SJ, Lee YG, Lee JM. An international comparison of sickness benefit programs. Health Soc Welf Rev 2021;41(1):61–80.

- 7. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Paid sick leave to protect income, health and jobs through the COVID-19 crisis. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/paid-sick-leave-to-protect-income-health-and-jobs-through-the-covid-19-crisis_a9e1a154-en.html. Updated 2020. Accessed May 13, 2025. Article

- 8. Edwards C. Low-paid workers to get 80% of salary in sick pay. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx28qw46p6yo/. Updated 2025. Accessed May 13, 2025.

- 9. Department of Enterprise, Tourism and Employment. Statutory sick leave in Ireland: an assessment of the impact of public policy changes post-pandemic. https://enterprise.gov.ie/en/publications/statutory-sick-leave-in-ireland-assessment.html. Updated 2025. Accessed May 13, 2025.

- 10. Mitchell SM. U.S. State Paid Sick Leave Laws. Issue Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 2024.

- 11. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 2024.

- 12. Gould E, Wething H. Access to paid sick leave continues to grow but remains highly unequal. https://www.epi.org/blog/access-to-paid-sick-leave-continues-to-grow-but-remains-highly-unequal/. Updated 2024. Accessed May 13, 2025.

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1.

| Country | Statutory paid sick leave | Sickness benefit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit | Coverage | Waiting period | Benefit period (max) | Financial resources (worker/employer) | Expenditure (% GDP) |

|||

| Non-regular workers | Self-employed | |||||||

| Australia | 10 days/regular workers | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 7 days | 9 months | Taxes | N/A |

| Austria | 16 weeks | 50%–75% | △ | × | N/A | 52 weeks | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Belgium | 30 days | 60% | ○ | ○ | 15–30 days | 1 year | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Canada | Varies by province | 55% | ○ | × | 7 days | 26 weeks | Worker < Employer | 0.1 |

| Chile (Private) | 3 days | 100% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | Worker | 0.1 | |

| Colombia | 2 days | 50%–66.6% | ○ | ○ | 2 days | 180 days | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Costa Rica | × | 60% | ○ | ○ | N/A | 26 weeks | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Czech Republic | 14 days | 60%–72% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 380 days | Employer | 0.8 |

| Denmark | 30 days | Flat-rate | ○ | △ | Self-employed (2 weeks) | 22 weeks | Taxes | 0.8 |

| Estonia | Days 4–8 | 70% | ○ | ○ | 9 days | 182 days | Employer | 0.5 |

| Finland | 10 days | 70% | ○ | ○ | 10 days | 300 days | Worker > Employer | 0.4 |

| France | 3 days | 50% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 12 months (3 years) | Employer | 0.7 |

| Germany | 6 weeks | 70% | ○ | ○ | 6 weeks | 78 weeks | Worker = Employer | 0.4 |

| Greece | × | 50% | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 720 days | Worker > Employer | 0.2 |

| Hungary | 15 days | 50% | ○ | ○ | N/A | 1 year | Worker < Employer | 0.5 |

| Iceland | 14 days | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 14 days | 52 weeks | Taxes | 0.0 |

| Ireland | 5 days (introduced in 2023) | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 6 days | 52 weeks (2 years) | Worker < Employer | 0.3 |

| Israel | 90 days | × | × | × | × | × | × | N/A |

| Italy | × | 50%–66.6% | △ | × | 3 days | 180 days | Employer | 0.2 |

| Japan | × | 66.67% | × | × | 3 days | 18 months | Worker = Employer | 0.1 |

| Korea | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | N/A |

| Latvia | Days 2–10 | 80% | ○ | ○ | 10 days | 52 weeks | Worker < Employer | 1.0 |

| Lithuania | 2 days | 80% | ○ | ○ | 2 days | 1 year | Employer | 0.8 |

| Luxembourg | 77 days | 100% | ○ | ○ | 77 days | 52 weeks | Worker = Employer | 0.4 |

| Mexico | × | 60% | ○ | × | 3 days | 52 weeks (78 weeks) | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Netherlands | 104 weeks | 70%–100% | ○ | × | N/A | 104 weeks | Employer | 0.3 |

| New Zealand | 5 days | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 2 weeks | 52 weeks reassessment | Taxes | |

| Norway | 16 days | 100%/75% (workplace/region) | ○ | ○ | 16 days | 52 weeks/248 days (workplace/region) | Worker < Employer | 1.0 |

| Poland | 33 days/14 days (under 50/50 or older) | 80%/70% (under 50/50 or older) | ○ | △ | 33 days/15 days | 182 days | Worker | 0.9 |

| Portugal | × | 55%–75% | ○ | △ | 3 days/10 days | 1,950 days/1 year (workplace/region) | Worker < Employer | 0.6 |

| Slovakia | 11 days | 55% | ○ | ○ | 11 days | 52 weeks | Worker = Employer | 0.8 |

| Slovenia | 30 days | 70%–80% | ○ | ○ | 30 days | No limits | Worker < Employer | 1.2 |

| Spain | Days 4–15 | 75% | ○ | × | 4 days | 12 months | Worker < Employer | N/A |

| Switzerland | 3 weeks–1 year | × | × | × | × | × | × | 0.9 |

| Türkiye | 7 days | 66.7% | ○ | ○ | 2 days | No limits | Employer | 0.8 |

| United Kingdom | Day 4–week 28 | Flat-rate | ○ | ○ | 3 days | 28 weeks | Taxes | 0.1 |

| United States | Varies by state government | × | × | × | × | × | × | N/A |

| Comprehensiveness of coverage (low) | Comprehensiveness of coverage (high) | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| (Ⅱ) Austria, Japan, Canada, Mexico, Netherlands, Spain | (Ⅰ) Belgium, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Türkiye | Adequacy of benefits (high) |

| (Ⅲ) (United States, Korea) |

(Ⅳ) Australia, Iceland, Ireland, New Zealand, Denmark, United Kingdom | Adequacy of benefits (low) |

The data were primarily based on the “Social Security Programs throughout the World” published by Social Security Administration (SSA) and International Social Security Association (ISSA) ( OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; N/A: not available; ×: Enrollment restricted; ○: Enrollment allowed; △: Optional enrollment. Public cash expenditure on sickness benefits as a percentage of GDP is from OECD SOCX (visited on April 19, 2025).

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The United States and Korea do not have both statutory paid sick leave and sickness benefit systems.

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite