Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 37; 2025 > Article

- Original Article Association between sudden work recall and psychological health issues: a cross-sectional analysis of the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey

-

Dong-Woo Kim

, June-Hee Lee

, June-Hee Lee , In-Ho Lee

, In-Ho Lee , Kyung-Jae Lee,*

, Kyung-Jae Lee,*

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2025;37:e33.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2025.37.e33

Published online: September 8, 2025

Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- *Corresponding author: Kyung-Jae Lee Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Hospital, 59 Daesagwan-ro, Yongsan-gu, Seoul 04401, Korea E-mail: leekj@schmc.ac.kr

© 2025 Korean Society of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 570 Views

- 21 Download

Abstract

-

Background The impact of global integration has led to an increase in non-standard work patterns, threatening workers' health. Psychological health problems, such as anxiety and fatigue, negatively affect workers' health and safety. Sudden work recall, a situation where workers are asked to return to work under unpredictable circumstances, is associated with uncertainty. Research on the relationship between sudden work recall and anxiety and fatigue is limited, and this study aims to investigate this relationship among Korean workers.

-

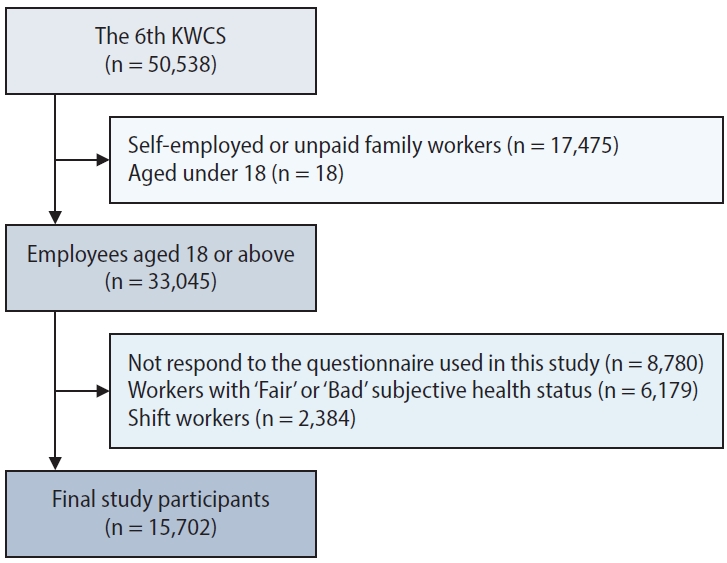

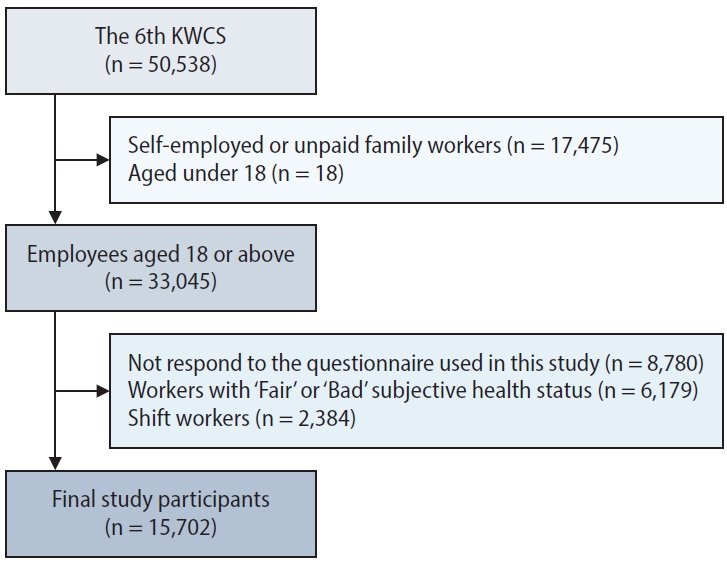

Methods The study used data from the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey. To analyze the pure effects of sudden work recall, the final sample was limited to 15,702 non-shift workers with a ‘good’ subjective health status. The presence of sudden work recall was categorized into three frequency groups: “several times a month,” “rarely,” and “never.” Anxiety and fatigue were each categorized into "yes" or "no" responses. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed.

-

Results After adjusting for demographic and occupational characteristics, the odds ratio (OR) for anxiety in the 'several times a month' group was 4.066 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.787–5.931), indicating a significantly higher risk. Conversely, the OR for the 'rarely' group was 1.363 (95% CI: 0.921–2.017), which was not statistically significant. A similar pattern was observed for fatigue: the 'several times a month' group had a significantly higher risk (OR: 1.875; 95% CI: 1.490–2.359), but the 'rarely' group (OR: 0.955; 95% CI: 0.750–1.215) did not.

-

Conclusions The relationship between sudden work recall and psychological health may not be a simple linear one. The results suggest that only a high frequency of sudden work recall is associated with an increased risk of anxiety and fatigue. Therefore, it is necessary to establish appropriate measures and to conduct additional research in this area.

BACKGROUND

METHODS

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

Abbreviations

-

Funding

This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund (JHL). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

-

Competing interests

June-Hee Lee, contributing editor of the Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Kim DW. Data curation: Kim DW. Formal analysis: Kim DW. Supervision: Lee JH, Lee IH, Lee KJ. Writing - original draft: Kim DW. Writing - review & editing: Kim DW, Lee JH, Lee IH, Lee KJ.

-

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute (OSHRI) and the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA) for providing raw data from the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey.

NOTES

| Variable |

Anxiety |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Sex | 0.815 | ||

| Male | 7,440 (97.1) | 226 (2.9) | |

| Female | 7,794 (97.0) | 242 (3.0) | |

| Age (years) | 0.307 | ||

| <30 | 2,307 (97.6) | 56 (2.4) | |

| 30–39 | 3,818 (96.8) | 126 (3.2) | |

| 40–49 | 3,969 (96.8) | 133 (3.2) | |

| 50–59 | 3,386 (97.1) | 100 (2.9) | |

| ≥60 | 1,754 (97.1) | 53 (2.9) | |

| Education | 0.359 | ||

| ≤Middle school | 941 (97.3) | 26 (2.7) | |

| High school | 4,927 (97.3) | 139 (2.7) | |

| ≥College | 9,366 (96.9) | 303 (3.1) | |

| Monthly income (10,000 KRW) | <0.001 | ||

| <200 | 4,052 (97.8) | 92 (2.2) | |

| 200–299 | 5,408 (97.0) | 170 (3.0) | |

| 300–399 | 3,344 (96.5) | 121 (3.5) | |

| ≥400 | 2,430 (96.6) | 85 (3.4) | |

| Occupation | 0.217 | ||

| White collar | 7,861 (96.8) | 258 (3.2) | |

| Pink collar | 3,433 (97.4) | 91 (2.6) | |

| Blue collar | 3,940 (97.1) | 119 (2.9) | |

| Weekly working hours | 0.138 | ||

| <40 hours | 2,595 (97.6) | 64 (2.4) | |

| 40–52 hours | 11,519 (96.9) | 365 (3.1) | |

| >52 hours | 1,120 (96.6) | 39 (3.4) | |

| Size of workplace | 0.001 | ||

| Small (1–9 workers) | 6,001 (97.5) | 155 (2.5) | |

| Medium (10–249 workers) | 6,672 (97.0) | 205 (3.0) | |

| Large (≥250 workers) | 2,561 (96.0) | 108 (4.0) | |

| Type of employment | 0.603 | ||

| Regular | 12,620 (97.0) | 392 (3.0) | |

| Temporary | 2,614 (97.2) | 76 (2.8) | |

| Sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| No | 12,395 (97.9) | 272 (2.1) | |

| Yes | 2,839 (93.5) | 196 (6.5) | |

| Frequency of sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| None | 12,395 (97.9) | 272 (2.1) | |

| Rarely | 2,466 (93.8) | 163 (6.2) | |

| Several times a month | 373 (91.9) | 33 (8.1) | |

| Variable |

Fatigue |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Sex | 0.250 | ||

| Male | 6,314 (82.4) | 1,352 (17.6) | |

| Female | 6,562 (81.7) | 1,474 (18.3) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||

| <30 | 2,076 (87.9) | 287 (12.1) | |

| 30–39 | 3,294 (83.5) | 650 (16.5) | |

| 40–49 | 3,320 (80.9) | 782 (19.1) | |

| 50–59 | 2,754 (79.0) | 732 (21.0) | |

| ≥ 60 | 1,432 (79.3) | 375 (20.7) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| ≤Middle school | 766 (79.2) | 201 (20.8) | |

| High school | 4,035 (79.7) | 1,031 (20.3) | |

| ≥College | 8,075 (83.5) | 1,594 (16.5) | |

| Monthly income (10,000 KRW) | 0.362 | ||

| <200 | 3,427 (82.7) | 717 (17.3) | |

| 200–299 | 4,584 (82.2) | 994 (17.8) | |

| 300–399 | 2,817 (81.3) | 648 (18.7) | |

| ≥400 | 2,048 (81.4) | 467 (18.6) | |

| Occupation | <0.001 | ||

| White collar | 6,828 (84.1) | 1,291 (15.9) | |

| Pink collar | 2,873 (81.5) | 651 (18.5) | |

| Blue collar | 3,175 (78.2) | 884 (21.8) | |

| Weekly working hours | <0.001 | ||

| <40 hours | 2,243 (84.4) | 416 (15.6) | |

| 40–52 hours | 9,790 (82.4) | 2,094 (17.6) | |

| >52 hours | 843 (72.7) | 316 (27.3) | |

| Size of workplace | 0.839 | ||

| Small (1–9 workers) | 5,062 (82.2) | 1,094 (17.8) | |

| Medium (10–249 workers) | 5,629 (81.8) | 1,248 (18.2) | |

| Large (≥250 workers) | 2,185 (81.9) | 484 (18.1) | |

| Type of employment | <0.001 | ||

| Regular | 10,737 (82.5) | 2,275 (17.5) | |

| Temporary | 2,139 (79.5) | 551 (20.5) | |

| Sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| No | 10,638 (84.0) | 2,029 (16.0) | |

| Yes | 2,238 (73.7) | 797 (26.3) | |

| Frequency of sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| None | 10,638 (84.0) | 2,029 (16.0) | |

| Rarely | 1,938 (73.7) | 691 (26.3) | |

| Several times a month | 300 (73.9) | 106 (26.1) | |

| Anxiety | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 1.338 | 0.907–1.976 |

| Several times a month | 4.032 | 2.769–5.870 |

| Model Ia | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 1.346 | 0.911–1.990 |

| Several times a month | 4.025 | 2.762–5.865 |

| Model IIb | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 1.363 | 0.921–2.017 |

| Several times a month | 4.066 | 2.787–5.931 |

| Fatigue | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 0.991 | 0.781–1.257 |

| Several times a month | 1.853 | 1.477–2.323 |

| Model Ia | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 0.989 | 0.778–1.256 |

| Several times a month | 1.922 | 1.530–2.414 |

| Model IIb | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 0.955 | 0.750–1.215 |

| Several times a month | 1.875 | 1.490–2.359 |

- 1. Kawachi I. Globalization and workers' health. Ind Health 2008;46(5):421–3.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Quinlan M. The Effects of Non-standard Forms of Employment on Worker Health and Safety. Conditions of Work and Employment Series. No. 67. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office; 2015.

- 3. Burton WN, Chen CY, Conti DJ, Schultz AB, Pransky G, Edington DW. The association of health risks with on-the-job productivity. J Occup Environ Med 2005;47(8):769–77.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Choi SC, Park HW. A study on the effects of employees' socio-emotional problems on stress, depression, and self-esteem. Korean J Soc Welf 2005;57:177–96.

- 5. Thorsteinsson EB, Brown RF, Richards C. The relationship between work-stress, psychological stress and staff health and work outcomes in office workers. Psychology 2014;5:1301–11.ArticlePDF

- 6. Lee HC, Yang EH, Shin S, Moon SH, Song N, Ryoo JH. Correlation of commute time with the risk of subjective mental health problems: 6(th) Korean Working Conditions Survey (KWCS). Ann Occup Environ Med 2023;35:e9.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Akerstedt T, Fredlund P, Gillberg M, Jansson B. Work load and work hours in relation to disturbed sleep and fatigue in a large representative sample. J Psychosom Res 2002;53(1):585–8.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Gomez-Salgado C, Camacho-Vega JC, Gomez-Salgado J, Garcia-Iglesias JJ, Fagundo-Rivera J, Allande-Cusso R, et al. Stress, fear, and anxiety among construction workers: a systematic review. Front Public Health 2023;11:1226914.PubMedPMC

- 9. Korani MF. The relationship between mental health disorders of depression, anxiety and job dissatisfaction among healthcare workers in southern region, Saudi Arabia. J ReAttach Ther Dev Divers 2023;6:555–65.

- 10. Jacobsen HB, Caban-Martinez A, Onyebeke LC, Sorensen G, Dennerlein JT, Reme SE. Construction workers struggle with a high prevalence of mental distress, and this is associated with their pain and injuries. J Occup Environ Med 2013;55(10):1197–204.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Cavuoto L, Megahed F. Understanding fatigue: implications for worker safety. In: Proceedings of the ASSE Professional Development Conference and Exposition; 2016 Jun 26-29; Atlanta, GA, USA. Park Ridge, IL: American Society of Safety Engineers; 2016, 16-9.

- 12. Barker LM, Nussbaum MA. Fatigue, performance and the work environment: a survey of registered nurses. J Adv Nurs 2011;67(6):1370–82.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Leon AC, Portera L, Weissman MM. The social costs of anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1995;(27):19–22.Article

- 14. Souetre E, Lozet H, Cimarosti I, Martin P, Chignon JM, Ades J, et al. Cost of anxiety disorders: impact of comorbidity. J Psychosom Res 1994;38 Suppl 1:151–60.PubMed

- 15. McCrone P, Darbishire L, Ridsdale L, Seed P. The economic cost of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in UK primary care. Psychol Med 2003;33(2):253–61.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Kim YH. Depressed mood experienced by domestic workers based on emergency call. M.S. thesis. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University Graduate School of Public Health; 2021.

- 17. Hancock PA. Reacting and responding to rare, uncertain and unprecedented events. Ergonomics 2023;66(4):454–78.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Peters A, McEwen BS, Friston K. Uncertainty and stress: Why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Prog Neurobiol 2017;156:164–88.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Ananat EO, Gassman-Pines A. Work schedule unpredictability: daily occurrence and effects on working parents' well-being. J Marriage Fam 2021;83(1):10–26.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 20. Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health: a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32(6):443–62.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Starcke K, Brand M. Effects of stress on decisions under uncertainty: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2016;142(9):909–33.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Morgado P, Sousa N, Cerqueira JJ. The impact of stress in decision making in the context of uncertainty. J Neurosci Res 2015;93(6):839–47.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Knutsson A. Health disorders of shift workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53(2):103–8.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Parent-Thirion A, Biletta I, Cabrita J, Llave OV, Vermeylen G, Wilczynska A, et al. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey: Overview Report. Dublin, Ireland: Eurofound; 2016.

- 25. Son SY, Min JY, Ryoo SW, Choi BY, Min KB. Association between multiple jobs and physical and psychological symptoms among the Korean working population. Ann Occup Environ Med 2024;36:e21.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 26. Jang YS, Lee JH, Lee NR, Kim DW, Lee JH, Lee KJ. Association between receiving work communications outside of work hours via telecommunication devices and work-related headaches and eyestrain: a cross-sectional analysis of the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey. Ann Occup Environ Med 2023;35:e50.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Orsini N, Li R, Wolk A, Khudyakov P, Spiegelman D. Meta-analysis for linear and nonlinear dose-response relations: examples, an evaluation of approximations, and software. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175(1):66–73.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: psychological and social resources as mediators. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54(3):486–95.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Le Blanc P, de Jonge J, Schaufeli WB. Job stress and health. In: Chmiel N, editor. Introduction to Work and Organizational Psychology: A European Perspective. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2000, 148–77.

- 30. Hall SJ, Ferguson SA, Turner AI, Robertson SJ, Vincent GE, Aisbett B. The effect of working on-call on stress physiology and sleep: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2017;33:79–87.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Baek C, Park JB, Lee K, Jung J. The association between Korean employed workers' on-call work and health problems, injuries. Ann Occup Environ Med 2018;30:19.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 32. Ronnblad T, Gronholm E, Jonsson J, Koranyi I, Orellana C, Kreshpaj B, et al. Precarious employment and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 2019;45(5):429–43.ArticlePubMed

- 33. Van der Doef M, Maes S. The job demand-control (-support) model and psychological well-being: a review of 20 years of empirical research. Work Stress 1999;13(2):87–114.Article

- 34. Mayerl H, Stolz E, Waxenegger A, Rasky E, Freidl W. The role of personal and job resources in the relationship between psychosocial job demands, mental strain, and health problems. Front Psychol 2016;7:1214.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 35. Schnall PL, Landsbergis PA, Baker D. Job strain and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Public Health 1994;15:381–411.ArticlePubMed

- 36. Akerstedt T. Psychological and psychophysiological effects of shift work. Scand J Work Environ Health 1990;16 Suppl 1:67–73.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Caruso CC, Waters TR. A review of work schedule issues and musculoskeletal disorders with an emphasis on the healthcare sector. Ind Health 2008;46(6):523–34.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Penuel WR, Means B. Using large-scale databases in evaluation: advances, opportunities, and challenges. Am J Eval 2011;32(1):118–33.ArticlePDF

- 39. Marks JS, Mokdad AH, Town M. The behavioral risk factor surveillance system: information, relationships, and influence. Am J Prev Med 2020;59(6):773–5.ArticlePubMedPMC

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Figure

- Related articles

-

- Health effects of weekend work on Korean workers: based on the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey

- Association between multiple jobs and physical and psychological symptoms among the Korean working population

- Association between single-person household wage workers in South Korea and insomnia symptoms: the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey (KWCS)

- Relationship between visual display terminal working hours and headache/eyestrain in Korean wage workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the sixth Korean Working Conditions Survey

- Association between receiving work communications outside of work hours via telecommunication devices and work-related headaches and eyestrain: a cross-sectional analysis of the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey

Fig. 1.

| Characteristic | No. (%) (n = 15,702) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 7,666 (48.8) | |

| Female | 8,036 (51.2) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 2,363 (15.0) | |

| 30–39 | 3,944 (25.1) | |

| 40–49 | 4,102 (26.1) | |

| 50–59 | 3,486 (22.2) | |

| ≥60 | 1,807 (11.5) | |

| Education | ||

| ≤Middle school | 967 (6.2) | |

| High school | 5,066 (32.3) | |

| ≥College | 9,669 (61.6) | |

| Monthly income (10,000 KRW) | ||

| <200 | 4,144 (26.4) | |

| 200–299 | 5,578 (35.5) | |

| 300–399 | 3,465 (22.1) | |

| ≥400 | 2,515 (16.0) | |

| Occupation | ||

| cccccccccuyc | White collar | 8,119 (51.7) |

| Pink collar | 3,524 (22.4) | |

| Blue collar | 4,059 (25.9) | |

| Weekly working hours | ||

| <40 hours | 2,659 (16.9) | |

| 40–52 hours | 11,884 (75.7) | |

| >52 hours | 1,159 (7.4) | |

| Size of workplace | ||

| Small (1–9 workers) | 6,156 (39.2) | |

| Medium (10–249 workers) | 6,877 (43.8) | |

| Large (≥ 250 workers) | 2,669 (17.0) | |

| Type of employment | ||

| Regular | 13,012 (82.9) | |

| Temporary | 2,690 (17.1) | |

| Anxiety | ||

| Yes | 468 (3.0) | |

| No | 15,234 (97.0) | |

| Fatigue | ||

| Yes | 2,826 (18.0) | |

| No | 12,876 (82.0) | |

| Sudden work recall | ||

| No | 12,667 (80.7) | |

| Yes | 3,035 (19.3) | |

| Frequency of sudden work recall | ||

| None | 12,667 (80.7) | |

| Rarely | 2,629 (16.7) | |

| Several times a month | 406 (2.6) | |

| Variable | Anxiety |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Sex | 0.815 | ||

| Male | 7,440 (97.1) | 226 (2.9) | |

| Female | 7,794 (97.0) | 242 (3.0) | |

| Age (years) | 0.307 | ||

| <30 | 2,307 (97.6) | 56 (2.4) | |

| 30–39 | 3,818 (96.8) | 126 (3.2) | |

| 40–49 | 3,969 (96.8) | 133 (3.2) | |

| 50–59 | 3,386 (97.1) | 100 (2.9) | |

| ≥60 | 1,754 (97.1) | 53 (2.9) | |

| Education | 0.359 | ||

| ≤Middle school | 941 (97.3) | 26 (2.7) | |

| High school | 4,927 (97.3) | 139 (2.7) | |

| ≥College | 9,366 (96.9) | 303 (3.1) | |

| Monthly income (10,000 KRW) | <0.001 | ||

| <200 | 4,052 (97.8) | 92 (2.2) | |

| 200–299 | 5,408 (97.0) | 170 (3.0) | |

| 300–399 | 3,344 (96.5) | 121 (3.5) | |

| ≥400 | 2,430 (96.6) | 85 (3.4) | |

| Occupation | 0.217 | ||

| White collar | 7,861 (96.8) | 258 (3.2) | |

| Pink collar | 3,433 (97.4) | 91 (2.6) | |

| Blue collar | 3,940 (97.1) | 119 (2.9) | |

| Weekly working hours | 0.138 | ||

| <40 hours | 2,595 (97.6) | 64 (2.4) | |

| 40–52 hours | 11,519 (96.9) | 365 (3.1) | |

| >52 hours | 1,120 (96.6) | 39 (3.4) | |

| Size of workplace | 0.001 | ||

| Small (1–9 workers) | 6,001 (97.5) | 155 (2.5) | |

| Medium (10–249 workers) | 6,672 (97.0) | 205 (3.0) | |

| Large (≥250 workers) | 2,561 (96.0) | 108 (4.0) | |

| Type of employment | 0.603 | ||

| Regular | 12,620 (97.0) | 392 (3.0) | |

| Temporary | 2,614 (97.2) | 76 (2.8) | |

| Sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| No | 12,395 (97.9) | 272 (2.1) | |

| Yes | 2,839 (93.5) | 196 (6.5) | |

| Frequency of sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| None | 12,395 (97.9) | 272 (2.1) | |

| Rarely | 2,466 (93.8) | 163 (6.2) | |

| Several times a month | 373 (91.9) | 33 (8.1) | |

| Variable | Fatigue |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Sex | 0.250 | ||

| Male | 6,314 (82.4) | 1,352 (17.6) | |

| Female | 6,562 (81.7) | 1,474 (18.3) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||

| <30 | 2,076 (87.9) | 287 (12.1) | |

| 30–39 | 3,294 (83.5) | 650 (16.5) | |

| 40–49 | 3,320 (80.9) | 782 (19.1) | |

| 50–59 | 2,754 (79.0) | 732 (21.0) | |

| ≥ 60 | 1,432 (79.3) | 375 (20.7) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| ≤Middle school | 766 (79.2) | 201 (20.8) | |

| High school | 4,035 (79.7) | 1,031 (20.3) | |

| ≥College | 8,075 (83.5) | 1,594 (16.5) | |

| Monthly income (10,000 KRW) | 0.362 | ||

| <200 | 3,427 (82.7) | 717 (17.3) | |

| 200–299 | 4,584 (82.2) | 994 (17.8) | |

| 300–399 | 2,817 (81.3) | 648 (18.7) | |

| ≥400 | 2,048 (81.4) | 467 (18.6) | |

| Occupation | <0.001 | ||

| White collar | 6,828 (84.1) | 1,291 (15.9) | |

| Pink collar | 2,873 (81.5) | 651 (18.5) | |

| Blue collar | 3,175 (78.2) | 884 (21.8) | |

| Weekly working hours | <0.001 | ||

| <40 hours | 2,243 (84.4) | 416 (15.6) | |

| 40–52 hours | 9,790 (82.4) | 2,094 (17.6) | |

| >52 hours | 843 (72.7) | 316 (27.3) | |

| Size of workplace | 0.839 | ||

| Small (1–9 workers) | 5,062 (82.2) | 1,094 (17.8) | |

| Medium (10–249 workers) | 5,629 (81.8) | 1,248 (18.2) | |

| Large (≥250 workers) | 2,185 (81.9) | 484 (18.1) | |

| Type of employment | <0.001 | ||

| Regular | 10,737 (82.5) | 2,275 (17.5) | |

| Temporary | 2,139 (79.5) | 551 (20.5) | |

| Sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| No | 10,638 (84.0) | 2,029 (16.0) | |

| Yes | 2,238 (73.7) | 797 (26.3) | |

| Frequency of sudden work recall | <0.001 | ||

| None | 10,638 (84.0) | 2,029 (16.0) | |

| Rarely | 1,938 (73.7) | 691 (26.3) | |

| Several times a month | 300 (73.9) | 106 (26.1) | |

| Anxiety | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 1.338 | 0.907–1.976 |

| Several times a month | 4.032 | 2.769–5.870 |

| Model I |

||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 1.346 | 0.911–1.990 |

| Several times a month | 4.025 | 2.762–5.865 |

| Model II |

||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 1.363 | 0.921–2.017 |

| Several times a month | 4.066 | 2.787–5.931 |

| Fatigue | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 0.991 | 0.781–1.257 |

| Several times a month | 1.853 | 1.477–2.323 |

| Model I |

||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 0.989 | 0.778–1.256 |

| Several times a month | 1.922 | 1.530–2.414 |

| Model II |

||

| None | Reference | |

| Rarely | 0.955 | 0.750–1.215 |

| Several times a month | 1.875 | 1.490–2.359 |

Values are presented as number (%).

Values are presented as number (%). Calculated using the chi-square test.

Values are presented as number (%). Calculated using the chi-square test.

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. Adjusted by demographic characteristics (sex, age, education, monthly income); Adjusted by demographic characteristics and occupational characteristics (occupation, weekly working hours, workplace size, type of employment).

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. Adjusted by demographic characteristics (sex, age, education, monthly income); Adjusted by demographic characteristics and occupational characteristics (occupation, weekly working hours, workplace size, type of employment).

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite